Kleshas: The coloring of the mind Part 3/3

This article is an excerpt from my book The Yoga Sutras Illuminated, published in May 2025.

In the previous two articles we discussed the meaning of coloring of the mind and the first four kleshas. In this concluding article we gain insights into the fifth and final klesha.

Clinging on to life

Abhinivesha is often translated as “fear of death,” however, it is not so much a fear of death, as it is clinging on to life as you know it. You cling on to all that you have: family, friends and material possessions. Whether you live in a mud hut or a palace, you don’t want to leave it. It’s a kind of inertia and even if someone is totally miserable, rarely do they commit suicide. Even those who are over ninety years in age and have lived well, struggle to leave this plane of existence gracefully. The fear experienced by the dying is not so much the fear of the unknown as it is the fear of loss. You don’t really fear death; you fear the loss of family, friends and opportunities to live out your unfulfilled desires.

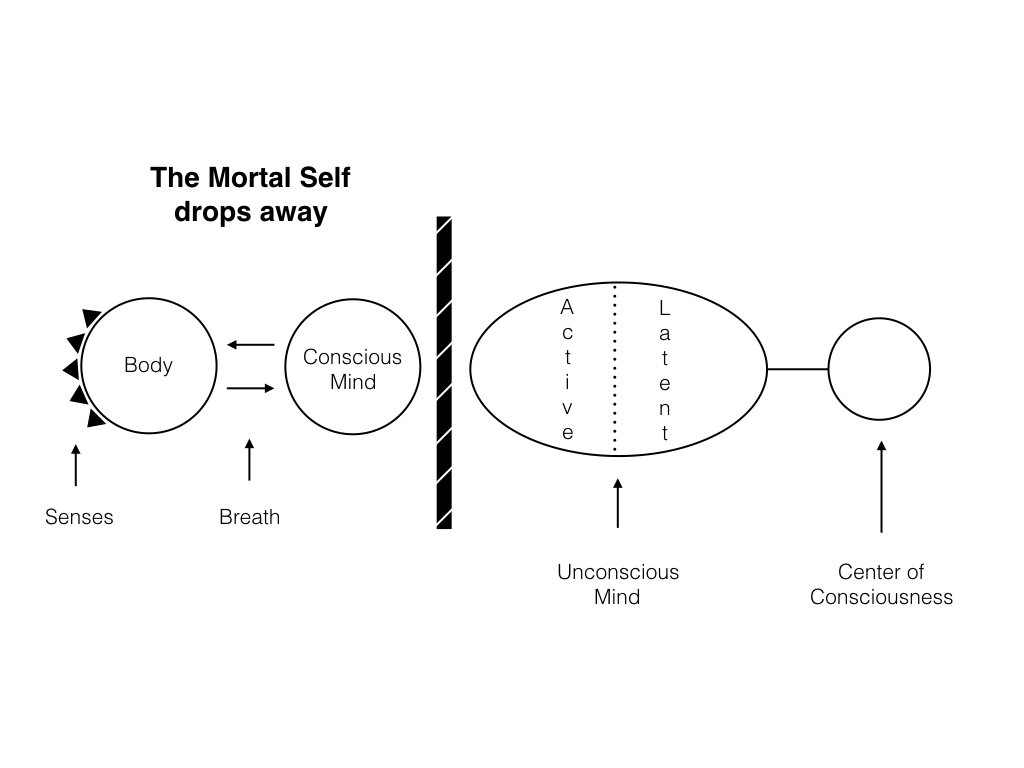

Fig. 1: Death is separation (Credit: Radhikaji & Sreeram Ramamoorthy

Death is separation

Thus, death is a separation from the life that is familiar to you. The mortal self, which is the body, senses, breath and conscious mind, drops away. When jivatman separates from the body and conscious mind, death occurs (Fig. 1: Death). If you focus only on what you know, that is, body and conscious mind, death will be terrifying. But if you choose to allow the hidden part of your mind to come forward, you will come to terms with this separation known as death.

Even if you don’t have a systematic practice that leads you inward to your true nature, it’s useful to familiarize yourself with the process of this separation intellectually. By now you’ve understood that the jivatman, that is, Individual Consciousness along with the active and the latent unconscious mind is semi-mortal. The active and latent unconscious mind are like a bed for the Individual Consciousness. This bed is made up of samskaras and when the conditions are suitable these samskaras grow into another body leading to rebirth. Once in its new body, the jivatman finds the new life unfamiliar. Yet, while the circumstances and surroundings may feel strange and confusing to the jivatman, its birth is akin to waking from a good night’s sleep. That’s why sleep is called sahodara, “the little sister” of death. In other words, death is really nothing more than a prolonged period of sleep, except that when you “wake up,” you are inhabiting a new body.

Sleep is the little sister of death (Credit: Hessam Nabavi, Unsplash)

These five kleshas may be:

Dormant (Prasupta)

Attenuated (Tanu)

Interrupted, (Vicchinna)

Active (Udaranam)

Depending on which type of klesha is at work, each samkara may be dormant, attenuated, interrupted or active. To understand a dormant klesha, we can use the example of a parent’s attachment to the child. Before someone becomes a parent, there is only the potential to become attached to a child in the future. So this klesha remains dormant, as long as you don’t have a child. When the child is born, the attachment becomes active. For instance, if the child is delayed on her way home from school, you may feel very worried; your attachment becomes very active while you are waiting. But once the child is safe at home, you feel more at ease because the klesha of attachment to your child is interrupted. Eventually the child grows into an independent-minded young adult. You now trust your child to handle situations in which she previously needed your help when she was still small and vulnerable. As a result, your attachment to the child reduces, that is, it has attenuated.

MY child (Credit: Gocha Szostak, Unsplash)

Attachment to sexual desires

Consider examining your relationships with different persons and objects to observe these four aspects of kleshas.

Let’s consider another example to understand the nature of coloring with respect to their intensity.

The attachment to sexual desires is also a klesha. In infancy, the desire for sex is dormant. At adolescence this desire gets active. When you develop a “crush” on someone as a teen, this klesha becomes highly active in the presence of this person. Yet, when the desired person is not around, this klesha is interrupted. This klesha naturally attenuates over time and you may observe that sexual desire decreases as you age.

Just as sexual desires are colored, so is our desire to cling to life. Fear of death results from this desire. However, unlike our attachment to sexual desires, abhinivesha tends to get more active over the course of a lifetime. In most children and young adults, the fear of death remains dormant. With increasing age it starts emerging from its dormant state.

Smashana means “cemetery” (Credit: Ruben Ortega, Unsplash)

Smashana vairagya, a temporary renunciation

We can observe the change in this klesha in everyday life. For example, if you pass the scene of a terrible accident, you get a rude shock. You drive carefully for the next few kilometers, because the klesha abhinivesha has become active. But, after a while, you drive fast again once the shock subsides; that is because the klesha is interrupted. Similarly, when you attend a funeral, you become very philosophical because encountering the death of another activates the deep-rooted impressions that make us cling on to life. This temporary phase is called smashana vairagya. Smashana means “cemetery.” So during this phase when the klesha can be especially active following the death of someone we know, we momentarily “renounce” our material attachments as we contemplate upon what lies beyond life as we know it. If the deceased was someone who was not a big part of your everyday life, then the abhinivesha klesha may revert to being dormant within a short time, as soon as you become absorbed again in your daily routine. Finally, as you grow older and your own death draws closer, you start thinking about death more often. At the final stages of life, the klesha is fully active. This klesha is active even in the wise who have devoted much of their lives to systematic meditation, thus illustrating the deep-rooted nature of our desire to cling to life. Therefore, it is advisable to learn a systematic method of meditation as soon as possible, ideally well before the fear of death becomes overly active. That said, no matter how old you are, it is never too late to learn how to practice systematically.

(Credit: Radhikaji)

The roasted seed

There is a fifth aspect of a klesha called ashukla-akrishna in Sanskrit. This mysterious klesha is likened to a “roasted seed.” Once a seed is roasted, then that particular seed—in this case, the samskara—no longer bears fruit. We may still engage in a relationship with that particular person or object, but since the klesha is completely uncolored, it no longer has the power to create any kind of bondage. As more of our samskaras are rendered impotent in this way, we increase our chances of attaining and maintaining Samadhi at will.

In practice, a meditator seeking Self Realization and following the path of systematic meditation begins by uncoloring raga and dvesha and not by attempting to work with avidya, the breeding ground of all colored mind patterns or with the fears of losing everything you know.